by Aileen Anthony

That ability—deliberate, categorical, and consistently repeated—explains why he could lose fortunes and rebuild them, why he took risks others avoided, and why he outlasted contemporaries trapped within a single worldview.

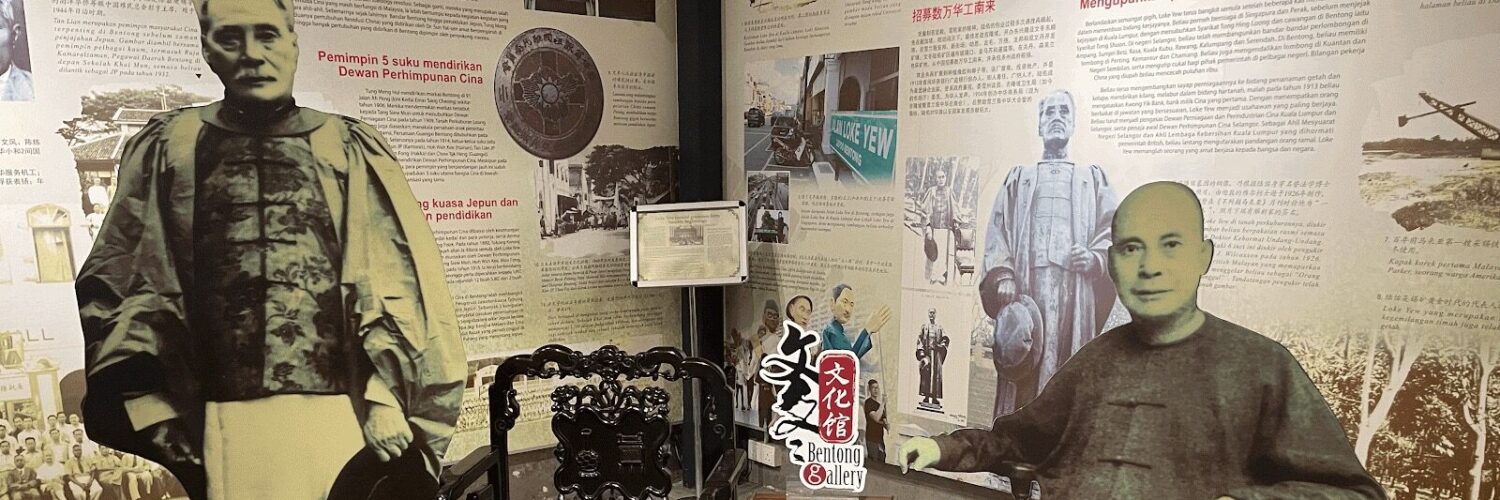

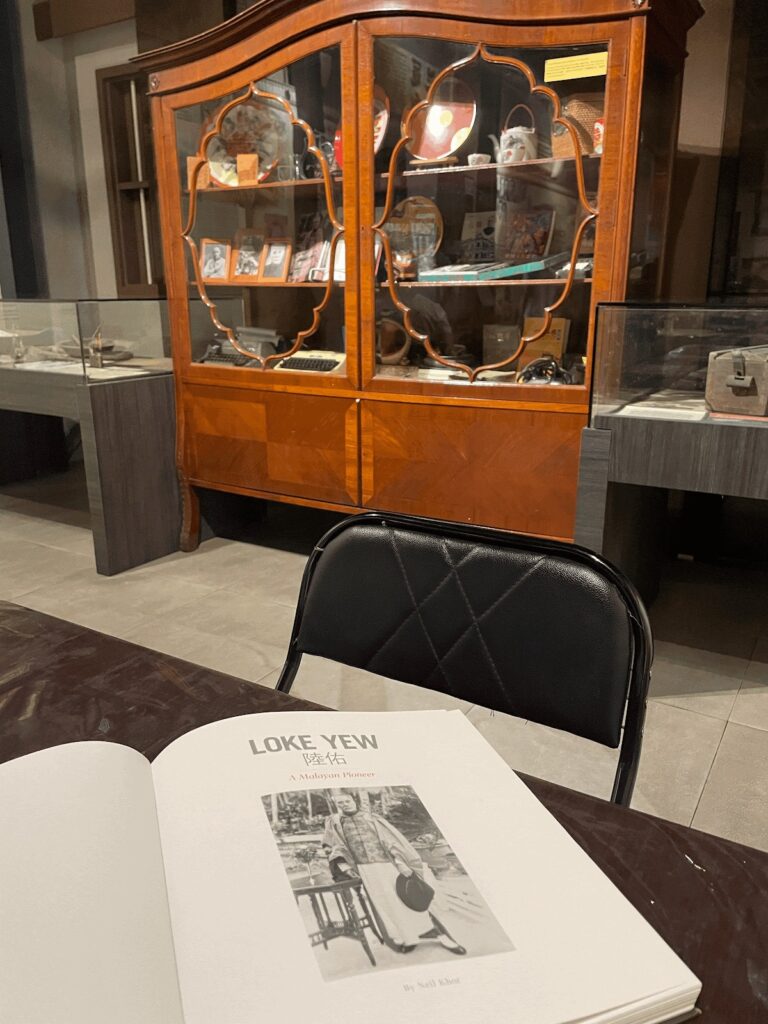

This understanding crystallised during my visit to Bentong Gallery, housed within the old shophouses along Jalan Loke Yew in Bentong, Pahang—once the centre of his business activities. The stop formed part of a Malaysia SME Congress practice hike in preparation for Mount Kinabalu. As with all such journeys, the hike was never just physical conditioning. It was a reconnection with local history, culture, and community.

What stayed with me was this: a historical figure from the turn of the twentieth century still bearing testimony to the enduring power of agility and adaptation—not just for survival, but for building a lasting business legacy.

Frontier origins shaped his earliest persona

Born Wong Loke Yew, he was a Malayan business magnate of Cantonese descent who played a significant role in the development of Kuala Lumpur and was among the founding figures behind Victoria Institution. After arriving in Malaya via Singapore as a teenager, he built his early fortune in Perak—particularly within the Larut and Taiping tin-mining landscape—before later emerging as a major figure in Bentong, Pahang.

Loke Yew’s entrepreneurial life began in a world where commerce, order, and influence were inseparable. This context shaped his earliest persona: pragmatic, resilient, and acutely aware that economic success in Larut depended on control—of labour, logistics, and alliances.

By the late nineteenth century, Larut was the Malay Peninsula’s most important tin centre, but also one of its most volatile. Rival Chinese secret societies, aligned with competing Malay chieftains, fought over mining rights and—crucially—over access to rivers that powered water-wheel pumps and enabled ore washing.

In this environment, Loke Yew’s first essential skill was not mining. It was reading the ground: understanding who held power, which resources truly mattered, and which alliances could endure.

Leadership revealed through logistics, not bravado

During the Larut tin wars (1861–1873), Loke Yew aligned himself with the Ghee Hin society. What distinguished him was not the faction he chose, but how he transformed chaos into a logistical problem that could be solved.

Tasked with breaking a Hai San blockade, he bypassed direct confrontation. According to Choo (n.d.), he recruited Orang Asli guides to transport rice through swamps between Bagan Serai and Krian, sustaining the Ghee Hin after a two-month journey.

This episode reveals his instinctive adaptability:

- He identified food supply—not force—as the real lever of power.

- He recruited beyond established Chinese networks.

- He treated terrain and time as strategic tools.

Here, Loke Yew demonstrated early mastery of selective logic—deploying the mindset best suited to the problem at hand rather than defaulting to tradition or ideology.

Rebuilding by shifting categories, not repeating tactics

After the Pangkor Treaty of 1874 imposed a fragile peace, Larut began transitioning from violent contest to administrative order. Loke Yew adapted swiftly, but without sentimentality.

His fortunes rose and fell in quick succession. He prospered in mining partnerships, lost heavily when mines were destroyed during the tin wars, recovered while working under Khoo Thean Teik in Kamunting, then suffered again when tin prices collapsed in 1874. Instead of retreating, he pivoted.

During the Perak War (1875–1876), he secured a contract supplying food to British troops—shifting from asset-heavy mining to cashflow-driven provisioning (Robson, 1934). With the support of Hugh Low, Resident of Perak, he later gained rights to operate revenue farms within the new colonial regulatory framework (The Straits Times, 1920; Butcher & Dick, 1993).

His adaptability was categorical:

- In frontier economies, power lay in manpower, muscle, and water.

- Under British administration, power lay in licences, leases, and compliance.

- Rather than resist the system, he entered it.

Positioning at the intersection of technology and trade

As Larut’s surface deposits depleted, the tin frontier shifted to the Kinta Valley. Loke Yew followed opportunity rather than geography, establishing ventures in Gopeng and Kampar. Contemporary accounts observed that once a district opened administratively, he was “on the spot” securing his interests (The Straits Times, 1931).

His most consequential leap, however, was psychological. While many Chinese towkays were wary of the Straits Trading Company (STC)—a British entrant with advanced coal-based smelting technology—Loke Yew supplied it with ore (Tregonning, 1962).

The decision paid off. By aligning with superior extraction technology and global shipping networks, he positioned himself at the convergence of industrial scale and international trade. He became an STC director by 1906, invested in shipping ventures including the Straits Steamship Company and the Aberdeen Steamship Company, and benefited as STC came to process roughly two-thirds of Malayan tin by 1912—about one-third of global supply (Sultan Nazrin Shah, 2024).

This was strategic placement.

From operator to mediator in Selangor

By the mid-1880s, Loke Yew relocated to Selangor. Initially active as a tax farmer while maintaining mining interests, he diversified into rubber and real estate. He co-managed the Selangor railway lease (1893), became the first president of the Selangor Chamber of Commerce (1904–1907), and increasingly served as intermediary between Chinese business communities and colonial administrators (Gullick, 2017).

His role had evolved. No longer just an operator navigating contested spaces, he became a public-facing mediator—requiring legitimacy rather than force.

Naturalisation was part of that alignment. On 18 May 1903, The Malay Mail reported that Loke Yew had been granted British naturalisation (The Malay Mail, 1903). This formalised his position within the colonial legal and economic order at a time when Kuala Lumpur was emerging as the administrative and commercial hub of the Federated Malay States.

Anticipating the next era

As the twentieth century advanced, British firms expanded through capital markets, deep-mining technology, and professional management. Many Chinese towkays struggled. Loke Yew anticipated the shift.

He increasingly relied on English-educated managers, European engineers, and professional advisers—some accompanying him to Europe. This was organisational foresight, not prestige. He was building a business capable of operating within a bureaucratic, technocratic Malaya.

Social networks reflected this transition. Loke Yew’s long-standing friendship with Dr Ernest Aston Otho Travers, Selangor’s pioneering colonial surgeon, marked his movement from transactional frontier alliances into the civic and institutional relationships that underpinned a more administered Malaya (The Straits Times, 1913; RIMBA, 1922).

The unifying thread

Viewed through the lens of adaptability and mindset-weaving, Loke Yew’s journey becomes coherent:

- He emerged from Perak’s frontier economy, where discipline and alliances ensured survival.

- He demonstrated leadership through logistics and terrain intelligence.

- He rebuilt repeatedly by shifting categories of wealth—from mines to contracts to licences to institutional partnerships.

- He aligned early with Western technology and global trade systems.

- He repositioned himself in Selangor as a mediator and community leader.

- He formalised alignment through naturalisation.

- He professionalised operations to match a changing administrative order.

Loke Yew wove—making disparate systems interoperable within one life. That is why he endured when others fell away. He was not confined to a single era. He became the bridge between them. For more information on Bentong Gallery, go to: https://bentong-gallery.com/

References

Butcher, J., & Dick, H. (1993). The rise and fall of revenue farming: Business elites and the emergence of the modern state in Southeast Asia. Macmillan.

Choo, K. P. (n.d.). The Late Towkay Loke Yew. Unpublished manuscript.

Gullick, J. M. (2017). A history of Kuala Lumpur, 1856–1939. Areca Books.

Robson, J. H. M. (1934). Malaya and the Malays. London.

RIMBA. (1922). Recreation Club in Kuala Lumpur. RIMBA Journal.

Sultan Nazrin Shah. (2024). Striving for inclusive development: From tin to tomorrow. Oxford University Press.

The Malay Mail. (1903, 18 May). Naturalisation certificate granted to Towkay Loke Yew.

The Straits Times. (1913). Farewell dinner for Dr E. A. O. Travers.

The Straits Times. (1920). Obituary of Towkay Loke Yew.

The Straits Times. (1931). Retrospective on early tin pioneers.Tregonning, K. G. (1962). Straits Tin: A brief account of the first seventy-five years of the Straits Trading Company. Straits Trading Company.